Insights

The US national debt burden

Share this article

October 14, 2024 | By Mesirow Currency Management

The debt level is approaching its 1946 historic high. Will it take a collapse in the bond or FX market before we take action?

Current US debt level

“How did your economy collapse?” the world asked. “Two ways,” the US said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

This version of memorable lines from Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises could describe what happens if the US fails to halt its swelling federal debt. Some think that a crisis is unlikely and that worries about the national debt are excessive and unnecessary. But everyone has the same question: what level of debt is too much?

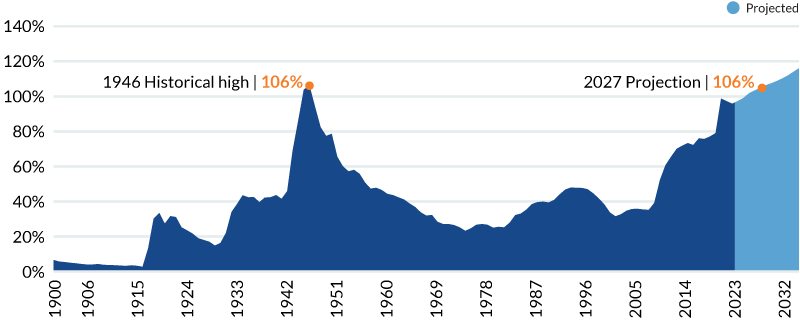

No one will argue that the current debt is historically high. The Congressional Budget Office, a nonpartisan federal agency that provides budget and economic information to Congress, estimates US publicly held debt at the end of the 2024 fiscal year (September 30) will be $28.2 trillion, equivalent to 99% of gross domestic product, a measure of the nation’s economic activity (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1: US DEBT HELD BY THE PUBLIC, 1900 to 2034 | % of GDP

Source: www.cbo.gov/publication/59710 for 1900 to 2024; cbo.gov/data/budget-economic-data (see 10-year budget projections June 2024) for years 2025 to 2034. Data for 1900 - 2023 are actual; 2024 to 2034 are projected.

CBO projects 2027 debt level will exceed its previous high set in 1946 after World War II, increase to 122.4% of GDP by 2034 and continue to rise. Reflecting these debt-to-GDP figures, at the end of June 2024, the public held an astonishing $27.6 trillion of federal debt, of which foreigners owned $8.2 trillion. Economists are troubled because excessive federal debt could mean government borrowing that crowds out more productive investments and lowers economic growth.

The CBO has expressed concern about federal borrowing. But in its An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook 2024 to 2034 published in June 2024, the CBO’s tone is neutral. The Update shows annual budget deficits, the difference between government revenues and outlays, to stay in a narrow range - 6.5% to 7.0% of GDP - for the next decade. The CBO estimates economic growth will slow from 3.1% in calendar year 2023 to 2.0% in 2024 and to 1.8% in later years. Inflation declines to the Federal Reserve's 2.0% target and interest rates fall from 2025Q1 to 2026 and gradually rise (Table 1). While not attributing low growth rates specifically to increasing debt, it's not hard to conclude that the increasing pile of IOUs is a drag on the economy.

TABLE 1: CBO ECONOMIC OUTLOOK | %

| 2023 actual | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027-28 Annual average | 2029-34 Annual average | |

| Real GDP | 3.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| Consumer Price Index | 3.2 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.2 | .2. |

| Unemployment rate | 3.6 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.5 |

| Interest rates (10-yr Treasuries) | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 4.0 |

Source: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/60039. Real GDP and CPI figures are the change from fourth quarter to fourth quarter; Unemployment and interest rates are annual averages.

The US debt and the 2024 election

We’re not worried.

Count the presidential candidates among those that aren’t overly concerned about budget deficits and resulting debt. Neither candidate has prioritized deficit-cutting measures in their campaign proposals or promises. Instead, Donald Trump and Kamala Harris look to expand the debt burden between $1.2 trillion to $5.8 trillion over the next decade.

Of course, what a candidate says while campaigning and what is enacted or ordered during the presidential term can be vastly different. Advice from advisors, feared market reaction, and changes in the economy might temper the urge to spend recklessly or cut taxes drastically. Still, the candidates’ proposals indicate that the federal debt is only headed up.

Paul Krugman, New York Times opinion columnist, professor and Nobel Prize winner in economics, isn’t too worried about the ballooning debt either. In a June 6, 2024 Times article, Mr. Krugman shrugs off the high level of debt, noting the current level is about the same as at the end of WWII and that it’s much lower than the level that Great Britain experienced a few years after that global conflict (210.7% of GDP in 1948) or the Japanese debt level (249% of GDP in 2023). The UK didn’t experience a debt crisis, and neither has Japan – yet. “America, with its huge economy and relatively low taxes, isn’t facing a fundamental problem of fiscal sustainability,” Mr. Krugman concludes.

US Treasuries ownership

Sure, we can finance that for you!

The US doesn’t lack for willing lenders, including foreign and international nations and investors, who have the largest share of publicly held debt.

TABLE 2: PUBLICLY HELD US TREASURIES OWNERSHIP, DECEMBER 2023

| Holder | Debt amount ($ billions) | Publicly held debt (%) |

| Federal Reserve (repurchase agreements) | $5,239 | 19.1% |

| Depository institutions | $1,653 | 6.0% |

| US savings bonds | $171 | 0.6% |

| Pension fund – private | $614 | 2.2% |

| Pension fund – state and local governments | $421 | 1.5% |

| Insurance companies | $477 | 1.7% |

| Mutual funds | $3,659 | 13.4% |

| State and local governments | $1,680 | 6.1% |

| Foreign and international | $7,941 | 29.0% |

| Other | $5,537 | 20.2% |

| Total publicly held debt | $27,329 | 100.0% |

Sources: https://fiscal.treasury.gov/reports-statements/treasury-bulletin/current.html, pgpf.org/blog/2024/08/the-federal-government-has-borrowed-trillions-but-who-owns-all-that-debt

Asian nations, most of them focused on exporting competitively priced goods to the rest of the world, the US in particular, have about a 37.7% share of foreign-held US debt. In a pattern called Bretton Woods II (the original Bretton Woods was the post-World War II international financial structure), the US buys goods from Asian countries who accumulate dollars, leading to an overvalued dollar, large reserves of US dollars at foreign central banks, and support for the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

The Bretton Woods II situation might intensify. China is hoping ramped-up exports will overcome a real estate bust that has weakened its economy. Unless the US counters with higher tariffs, China’s low-cost products could entice US consumers to buy more Chinese goods, sending more dollars to China and increasing its $1 trillion stockpile of US currency (mainland China $780.2 billion plus Hong Kong $220.6 billion).

Many analysts believe that China and other Asian nations are committed to continuing the Bretton II arrangement indefinitely because these creditor nations benefit from export-centric economies. They spur this export situation by keeping their exchange rates with the US dollar low – until the recent tumble in the US dollar based on investor expectations of interest rate cuts in the last months of 2024 – so that their exports remain inexpensive and competitive with US producers.

Foreign debt holders

It won’t go on forever although we wish it would.

Eventually, however, China and other foreign holders of US treasuries will nervously view their portfolios of government bonds and bills issued by a nation that seems unwilling to address its budget deficit and ever-expanding accumulation of debt. It is unreasonable to expect that foreigners will continue to finance the US deficit at interest rates that don’t adequately compensate them should the dollar fall and US interest rates rise.

These foreigners might reduce their portfolio of bonds and bills in an orderly manner, causing interest rates to rise and the US dollar to decline modestly each year. That scenario is optimistic. More likely, a trickle of increased selling might suddenly become a deluge as US treasury holders raced to sell their US bonds and bills before everyone else. Panic might be too tame of a word to describe the market rout.

The result: former creditor nations would have more expensive currencies (they sold US dollars gained from the sale of treasuries and bought their home currencies), causing their exports to be more costly. The US would increase interest rates to finance the budget deficit. A recession with high unemployment and reduced consumer spending and investment would free up domestic savings to help finance the US budget deficit.

Debt level projections

Question: So how much debt is too much debt? Answer: 175% to 200% of GDP

That’s according to the Penn Wharton Budget Model, a non-partisan research group that provides public policy fiscal analyses. A debt level of 200% of GDP is far in the future, past the CBO’s 30-year publicly held debt projection of 166% of GDP in 2054. But 200% of GDP is a best-case scenario; a more likely debt limit is 175% of GDP, which is close to the estimated 2054 public debt level.

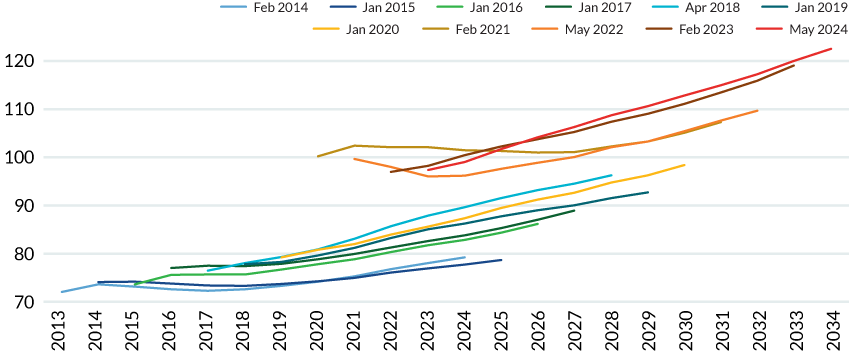

It’s probably even closer because CBO estimates of publicly held debt typically increase every time statistics are revised. The curves generally move up, meaning an increase in debt to GDP (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: CBO ESTIMATES OF PUBLICLY HELD DEBT AS PERCENT OF GDP, FISCAL YEAR 2014 - 2024

Figure 2 shows CBO estimates of publicly held debt rising each year from 2014 to 2024.

Source: Penn Wharton Budget Model, all years except 2024: budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2023/10/6/when-does-federal-debt-reach-unsustainable-levels, 2024: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59014

It’s unlikely financial markets would wait until debt to GDP reaches 175% to 200% before reacting. Convinced much earlier that the government is unwilling to address the debt issue, holders would dump their US treasuries well before the upper limit of debt was reached.

Could the US default?

Yes.

The US could default on its debt explicitly, unwilling to pay interest or principal. Or default might be implicit: the US government would coordinate with the Federal Reserve to buy treasuries on the open market, creating capacity for the Treasury to issue more debt. The Federal Reserve actions would increase the money supply and likely result in higher inflation so that the US government would pay interest and principal with inflated US dollars.

People understand the pitfalls of too much debt and recognize that a limit exists as to how much lenders will give them. A limit applies to nations too, and the US seems determined to find it. The hope is that reasonable politicians and government officials will work together to, at a minimum, stabilize the debt well before that limit is reached.

Explore more currency insights

Rapid payments speed money through the financial system; economic growth follows

Will developed countries follow the instant payment lead of developing countries?

US debt is headed to unimaginable levels

Since 1990, debt crises have erupted periodically, but the next one may not be so easy to dismiss. Is a financial reckoning coming?

Spark

Our quarterly email featuring insights on markets, sectors and investing in what matters